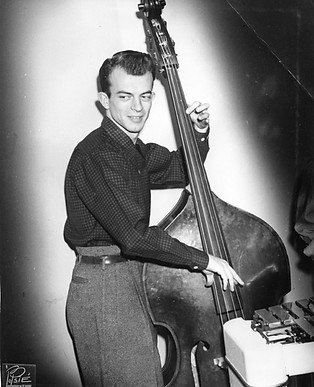

BILL CROW

Bassist for Benny Goodman’s orchestra

during the USSR tour

I remember the words 'spasibo,' 'morozhennoe,' and 'poehali' – those were the ones I kept saying all the time back then.

What were your first impressions of the Soviet Union?

When we landed at the airport in Moscow, I noticed that the trees around looked very much like those in Washington State, where I grew up. I thought, ‘This feels familiar. The same latitude. A different part of the world, but similar nature.’ Of course, I knew many Russian immigrants in New York and had an idea of what Russians looked like. So when I started meeting people in the Soviet Union, the only real difference I noticed was in the way they dressed and the old buildings around. The architecture was unique and unlike anything I had seen before. Otherwise, I felt right at home, though I couldn’t speak Russian. It’s a difficult language. But I had a little booklet from the U.S. State Department, prepared for diplomats, which explained the Cyrillic alphabet and how to pronounce letters and words. I studied it constantly. I also had a notebook for recording phrases. After a couple of weeks in the USSR, I could read names of metro stations and recognize words I had heard before.

Since I started working in the music business and traveling around the world, I’ve always been interested in where I’m going and looking to see what’s happening around me. You could say I’m a good tourist. While I was in the Soviet Union, I would get up around six in the morning every day and go for a walk. I had a good sense of direction, so I could find my way back to the hotel. Of course, there were guys in similar suits who clearly kept an eye on us, especially around places where musicians gathered. But they didn’t seem to like getting up early, so I never noticed anyone following me in the mornings. At concerts and in the hotel, though, we often saw such people. They looked like store detectives, like the ones at Macy’s, watching to make sure no one shoplifted. But overall, everyone I met was very friendly and welcoming, and I truly enjoyed being there.

How did the audience receive you?

It was interesting. In most of the places we played, real jazz was still unfamiliar. So real jazz fans came, but at the first concert in Moscow, the audience was very restrained, clapping politely without much enthusiasm. Then I realized that the hall was full of officials – only they could get tickets to Benny Goodman’s first concert in Moscow. This went on for about three days. At the first concert, Khrushchev himself was present, and naturally, if he didn’t clap, no one else did. But starting from the third or fourth concert, enthusiasm began to grow, and we started meeting true jazz fans.

Leningrad was magnificent. There was a rich cultural atmosphere there, which wasn’t as evident in Moscow. It’s like any major city with a university – people are interested in jazz because they are interested in the arts. In Sochi, we were also warmly received. The audience was festive and ready for entertainment, and they were happy to see us. Tbilisi was interesting: the audience welcomed us warmly, but when singer Joy Shell started singing a Russian song, they expressed displeasure because they wanted to hear a Georgian song. That’s how we understood there were cultural differences among the regions. But we were treated wonderfully. One day, we were taken out of town for kebabs, and after the first concert, they invited us to a hall with great acoustics on a hill, where they treated us to wine and food. That’s where we learned about the tradition of giving toasts.

Did you get drunk?

Oh, yes! I’m actually not much of a drinker – a beer a day is my limit. But there, I would fill my wine glass with strawberries and pretend I was drinking along with everyone else. One of the saxophonists, known for his tolerance to alcohol, once said, ‘I practice when I’m drunk.’ He waited until everyone had given their toasts, then he made his own eloquent toast. That was a good lesson.

When we got to Uzbekistan, however, the audience was quite cool towards us. Benny was disappointed and shortened the program, and soon we flew back to Leningrad. It was a different culture, and people there just weren’t ready to appreciate that kind of music.

What was the story with the singer Joya and Benny Goodman?

Joya was engaged for the tour as a featured vocalist, which was different from the traditional setup where the band had a 'girl singer' who only performed a part of the set while the band remained the main attraction. Benny was used to this older approach. Joya had her own arranger who created a whole set of songs specifically for her, and we rehearsed it at the Seattle World’s Fair before the tour. However, Benny started pulling out songs from his 1936-37 repertoire, expecting her to perform them like a standard band singer. Joya told him, 'Mr. Goodman, I’m not just the band singer; I’m a featured vocalist with my own repertoire.' From that moment, they stopped speaking, and throughout the tour, Benny was somewhat undermining her.

Despite this, she was incredibly successful. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone like her on stage. She had an opening number that was vibrant and lively, written especially for her. The second number had a bass line that I would play, and she could come in at any point as the applause faded. She loved that. But by the time we reached Russia, Benny had removed her opening number. He would announce her, but instead of running onstage, she’d walk out, come over to me, and wait for Benny to pick up the tempo before giving me a cue to start. The whole vibe of the performance was dampened compared to how it was originally set. Still, she had great success, and the audience adored her, which didn’t sit well with Benny. He always seemed to be in subtle competition with his musicians, even though he hired only the best.

At the end of the tour, Benny instructed George Avakian not to include Joya on the album he was producing from the tour. Her name didn’t even appear in the lineup, as if she hadn’t been part of the tour at all. All of her performances were recorded but are still sitting in the Connecticut archive. Maybe someday an album will be released because she sang beautifully, and we all enjoyed performing with her. It’s truly a shame that the recordings were made but never published.

Yes, Benny played well. We were all thrilled to be there because we were all fans of Benny Goodman. But we also had our self-respect, which Benny sometimes seemed to test. He would say things to people, shuffle players in the trumpet section, change who played which solo—things like that. My attitude was, 'We came to play for you, and we admire the band.' But there was a certain tension between him and the rest of the musicians. Phil Woods, for example, was a brilliant clarinetist and the lead in the saxophone section. Zoot [Sims] was probably the most famous among them. Benny respected Zoot’s playing but felt competitive with him, while Phil’s skill was perhaps too close to Benny’s own, and he didn’t appreciate the competition.

How did you react to the news about the Cuban Missile Crisis?

Fortunately, I was in Paris during the missile crisis. We heard about it second-hand from French-speaking friends who were helping us navigate the experience. We were mostly occupied with music, so it didn’t seem like a big deal at all in Paris. However, when we returned to New York, we discovered that everyone there had been terrified, thinking World War III was about to start. That’s when we realized how tense things really were. By the time we got to Russia, Khrushchev had already made his famous shoe-banging statement at the UN.

We hoped that our tour might help ease some of the tension, and it seemed to have that effect. Khrushchev himself even came to one of our concerts, although he didn’t have a high opinion of jazz and didn’t think it was good music. But we saw his remarks as merely political statements. Overall, the people we encountered—the audiences, staff, interpreters, and even officials—showed us kindness and a positive attitude. In fact, our main difficulties on the tour came from Benny rather than from the Russians. Some people are easy to get along with, while Benny sometimes chose to make things challenging. Despite that, the band sounded fantastic, and we were proud of it."

He allowed the State Department to spend a lot of money on having new arrangements written for the band, hiring some of the best jazz arrangers in New York. We used some of these fresh pieces to open the concert. But Benny wasn’t particularly enthusiastic about having new music on stage; he was used to his old songbook and preferred to play everything from memory. He liked to return to the older material simply because he felt more comfortable with it, even though we had such great music to play.

How did you learn about the upcoming tour in the USSR?

When we first heard that the State Department was planning to send a jazz band to the Soviet Union, almost everyone in the jazz world immediately thought that Duke Ellington would be the ideal choice. I don’t know if Duke himself was interested, but it seems the Russians weren’t particularly thrilled about the idea. Ellington's band was all Black, and just before that, there had been a riot at the Newport Jazz Festival. Jazz fans had nothing to do with it—the trouble was caused by rock 'n' roll fans trying to get in for free and knocking down fences, creating a huge mess. The media blew the incident out of proportion, making it look worse than it actually was, and by the time the news reached Russia, people there couldn’t distinguish between rock 'n' roll and jazz, so it became known simply as a 'jazz riot.' The story lingered for quite some time.

So, the State Department suggested Benny Goodman as an option, noting his classical background. He had studied with a classical clarinetist and recorded some classical music, which helped make him seem more suitable. They thought Benny could perform not only with his own orchestra but also play clarinet concertos with the Moscow Philharmonic. I think Benny wanted to do it, but he wasn’t as prepared as he probably should have been. Once he arrived, he kept changing his mind, saying he would play Stravinsky instead of Mozart and so on. This went on for a few days, and he kept sending updates to the Philharmonic, who eventually felt he was just toying with them and canceled the concert. This caused a huge stir at the State Department, as they needed Benny to perform something classical per the arrangements they had made.

They then found out that Byron Jennings was performing in Leningrad and persuaded him to stay a few extra days until we arrived, so he could perform 'Rhapsody in Blue' with us. However, it turned into a fiasco because Benny didn't take it seriously. I detail this story in my book—you’ll have to read it again. Unfortunately, that’s how it went. Benny was chosen precisely because of his classical credentials, which gave him an added layer of respectability.

Actually, we did a retrospective of popular big band music, which felt somewhat out of place since we were there to perform our best music. There was plenty of good music available without needing to revisit Glenn Miller or Tommy Dorsey. But in each concert, we did include a little piece, and it seemed to make some people happy, although the band itself wasn’t particularly interested.

Did you know anything about Russia before the tour?

I only knew what I’d read in newspapers or seen in news releases, which were likely quite slanted. But I had learned a bit from Russians living here. I’d also visited a Russian restaurant in Greenwich Village, where I discovered Russian cuisine, and I was familiar with Russian composers I admired, along with Russian culture, ballet, and so forth.

Our reception in Russia was remarkable. They even arranged a special afternoon ballet performance just for our band, which was wonderful. We visited many artistic sites—they took us to museums regularly. But it seemed that those organizing our visits didn’t fully grasp that, while we were a band, we were not a collective in the Soviet sense. For instance, in the hotel, they’d ask, ‘Would you like a soft-boiled egg for breakfast?’ and if one person said ‘No,’ they assumed no one wanted it. Or they’d ask, ‘Would you like to go to a museum today?’ and when I’d say, ‘Oh, I’d love to go!’ they’d bring a bus and ask, ‘Where’s the rest of the band?’ They didn’t quite get that we were individuals with unique tastes.

One memorable experience was in a museum in Leningrad, which had a floor dedicated to abstract and modern art from the 1920s. Every time I went, that floor was closed. But on our last day, they told us the bus would depart at 10 instead of 8, so I thought, ‘Great, maybe the museum will be open.’ And to my surprise, it was! I was thrilled to see the Picassos and other pieces there. I enjoyed the museums across Russia, as they held works I’d only seen in books.

They also took us to Petrodvorets and even let us interact with the fountains, which was fascinating, especially seeing how meticulously they’d restored everything.

Did you interact with jazz fans in the USSR?

We met a few fans in each city we visited, except Uzbekistan—I don’t remember anyone there, maybe just one guy. But in the other cities, they’d come to the hotels, attend concerts, and tell us where we could go afterward to play or hear music. It’s always interesting; music is like a lingua franca. Even if you don’t understand each other’s language, you can play together. It’s amazing!

Did you participate in jam sessions with Soviet musicians?

Yes, I did—I was playing bass. We would go to restaurants where musicians were performing or sometimes to places with a piano. In Leningrad, they invited us to a university building, and we played there one night. It was a funny journey because our cab driver couldn’t find the address. A police officer came over, and the driver warned us not to speak English, or he’d take us to the station. The officer explained that some of the building numbers were inside a courtyard, and we finally got there. The young musicians had been waiting for us. We started playing around 11 p.m., but I think we finished by then, because after a certain hour, the bridges went up, and we couldn’t get back to the hotel.

Do you remember any specific Soviet musicians?

I remember two of them well: trumpet player Konstantin Nosov, who played excellently, and alto saxophonist Gennady Goldshtein, who was also fantastic. There was another musician, maybe in Tbilisi, who showed Phil Woods an alto sax he’d carved from black wood himself since he couldn’t buy one. Phil tried it, shook his hand, and congratulated him. I don’t know how it sounded, but musicians there faced many challenges in getting supplies. For instance, in Sochi, I once sent a musician bass strings, a bridge, and sheet music. It was easy for me to send packages, knowing how much it meant to them.

Did they give you any instructions before the trip?

Certainly, the U.S. Embassy in Moscow gave us a thorough briefing on how to behave during the tour. They warned that some American journalists had already been set up in compromising situations that could later be used for blackmail. We were advised to avoid any compromising situations and not to go anywhere alone. We followed this advice.

At the concerts, there was concern that the audience might get out of control or try to storm the stage, maybe based on what they had seen in Hollywood movies. Because of this, serious-looking people in uniform, or at least very stern guards, always stood at the edge of the stage to keep everyone in check. At one point, a woman approached the stage to present a bouquet of flowers, almost like in a theatrical scene.

In the U.S., Benny never stayed at the same hotel as the orchestra. He preferred to keep his distance and even insisted on staying on a different floor in our hotel in the USSR. But when they started filming a documentary about the band’s tour in Russia, we were invited to sit with him at one table to take group photos. It was a bit childish of him.

In Russia, Benny was with his family, and one of our translators was assigned to his group, leaving us with only one, though they later sent a second interpreter. They were very helpful, showing us around and explaining things.

Did you know that the jam session at the university was technically illegal?

No, we didn’t know it was illegal, but we understood that if the university’s administration had found out, they probably wouldn’t have allowed it. We did what we were told by others, and sometimes we didn’t fully understand the situation. There was one fan who kept hanging around backstage to chat with the musicians, and he was detained. It was disappointing to see that — he was just a jazz fan and nothing more.

Did you encounter KGB agents?

I’m not sure, as they didn’t introduce themselves, but there were always men in blue suits standing around the hotel and watching us. They looked like store security guards — you can recognize that type by their appearance.

Was it risky for Soviets to establish contact with foreigners?

Once, I met a young woman who worked in television, possibly as an announcer. She invited me to her place, but when I arrived, she looked very frightened. I told her, "If this isn’t a good idea, I can leave," and I did. She seemed to hope that I could somehow change her life, but I had no such intention. I think she wanted to reach out to another world, but she was too scared.

Did you have any issues during the tour?

As we were leaving, they searched my suitcase and found small film canisters with sand samples I had been collecting for my father, an amateur geologist. In each city, I would gather a bit of sand, but during the customs inspection, they seized all my samples and my film reels. I had an old Kodak camera with large film cartridges, and I think they assumed it was some kind of spy equipment. Ten years later, I found out that all my films had been destroyed, but they analyzed the samples and found that one of them — from a beach in Sochi — was slightly radioactive.

Did you encounter KGB agents?

I’m not sure, as they didn’t introduce themselves, but there were always men in blue suits standing around the hotel and watching us. They looked like store security guards — you can recognize that type by their appearance.

Did you get paid well for the tour?

Yes, I asked for the highest amount I’d ever been paid to ensure it would be a fair salary. Later, I learned that whenever I spoke to his manager, Benny was on the other line, listening in. The manager would tell me, “I’ll get back to you,” and then call back in five minutes saying, “Benny agrees, but he’ll need the recordings.” That meant I wouldn’t be paid royalties for any recordings they released. I wasn’t aware of the union rules at the time, but I agreed because I wanted to go on the tour. I didn’t feel underpaid, though I knew some guys in the band were making more — but I’ve never been great at squeezing out every last cent.

What do you think about the current relationship between Russia and the United States, as it seems like we're in a Cold War again?

It seems to me that it would be wonderful if art could determine relationships between countries, rather than power and money, but it’s always about power and money. Some people can be more relaxed about these things, while others feel they need to control everything. People are fortunate if their government isn’t oppressive, as that makes life much easier, but I don’t know how to bring that about. In my experience, individuals, even those I disagree with politically, tend to be more open when it comes to art. Music can make people happy; it makes me happy, and I think that’s a good place to start.

Do you think there's a misunderstanding between Russians and Americans?

There’s always misunderstanding due to the information people are fed. These days, we talk a lot about “fake news,” but misinformation has been around for centuries. For instance, during World War II, we were enemies with Germany and Japan, and the media portrayed Germans and Japanese as monsters, which didn’t align with my own experiences with Germans and Japanese I knew here. I grew up on the West Coast, where many Japanese immigrants ran farms, and they were all swept away to internment camps during the war because people were afraid of the Japanese. But now, suddenly, Japanese people are okay again. It’s strange. As for Russia, I think it’s a beautiful country, full of wonderful, interesting people. It would be a tragedy if politicians destroyed that, but I don’t know how to prevent it.

You were the only musician from the band who wrote a book about the tour in Russia. Tell us about it.

I forgot to mention a few musicians from the tour, like our guitarist (name needed). He was from Yerevan and even managed to find some family members he hadn’t seen for decades. He was thinking of writing a book about the tour and kept notes throughout, but nothing ever came of it. Years later, I was in touch with jazz writer Gene Lees, who encouraged me to tell the story, saying, “Nobody’s written about that tour.” I told him I could do it if he wanted, and he encouraged me to write as much as I liked. So, I reached out to (guitarist) to ask if I could read his manuscript, but he said he’d given it to Zoot, who had passed away. I ended up calling Zoot’s widow, who knew where it was and shared it with me. It was a treasure — like a diary, full of names, dates, and sequences, which was very helpful when I was putting the story together. Gene decided to publish it, and when Benny Goodman was still alive, he even gave me some editorial suggestions. Just as we were ready to print, Benny passed away. Gene asked if I thought it was too soon to publish, but I said, “If it’s true, then it’s worth sharing.” The fans of Benny Goodman weren’t too pleased with it, but people like Margaret Whiting thanked me for telling the truth.

You titled the book "To Russia Without Love." Was that how you felt?

Not really. There was a James Bond movie called From Russia with Love, so I played off that title. I called it To Russia Without Love because Benny gave us so much trouble on the tour.

Did anything interesting happen in Kyiv?

I remember going to the beach there, which was our first chance to swim. We lay on the beach with loudspeakers playing music all around. A young Russian man sat down beside me and wanted to know everything about America. He asked if it was true that it was hard to get a passport in the U.S. because he’d heard that thousands of people couldn’t get one. I explained that Americans only get passports when they’re planning to travel. He was surprised, as in the USSR, you needed a lot of documents just to prove where you worked.

I ask because there’s a town near Kyiv called Bila Tserkva, where Benny’s parents were from.

It seems he wanted to perform there but was not given permission.

Everywhere we went, people tried to talk to us. The guy on the beach in Kyiv was funny — first, he asked if I had any nylon to sell! He had a very romanticized idea of the U.S.

Did you gain a better understanding of Russia after the tour?

Absolutely. When I talk about Russians, I’m talking about the individuals I met, not the government. This was many years ago, but I still feel very warmly about the people there. One of the most interesting experiences happened in Tashkent. I had my hotel key with the address and was trying to keep track of where I was. Tashkent, with its palm trees and old walls, looks the same everywhere, so it’s easy to get lost. I walked into a market to buy some souvenirs, but when I tried to leave, I saw four identical doorways and didn’t know which one led back. I walked around for a while and finally saw a taxi. The driver started speaking to me in Uzbek, thinking I was local because I was wearing a traditional Uzbek cap. I told him, “American music,” and he laughed, saying, “Get in!” He drove for a while, then stopped near a trolleybus stop and motioned for me to get on. When I tried to pay, he wouldn’t take the money. I boarded the trolley, and after what felt like a 15-mile loop, it finally brought me back to the concert hall and hotel.

During a jam session in Leningrad, Soviet musicians gave their American counterparts sheet music with Soviet compositions.

Do you remember this?

I don’t recall receiving any myself, but I think Phil Woods did. When we returned, someone from Radio Liberty reached out, saying they wanted to send supplies to Russian musicians. I collected items like reeds, strings, and instruction books, and we sent them to three musicians. They then asked if I would record some pieces by Soviet jazz composers. They were generous, so I thought, why not? I put together a small band, and we recorded the music. I still see those records in music shops today.

IWe’ve found people in Russia who attended your concerts and still talk about them.

Some even compare the experience to Gagarin’s spaceflight. What do you think of that?

I think that’s someone else’s feeling to comment on.

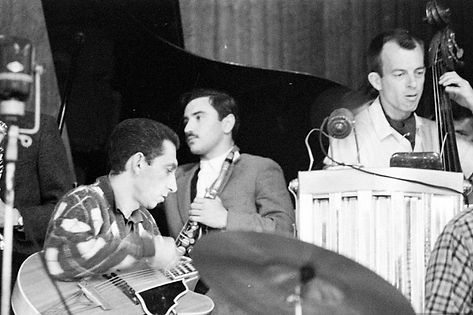

Photos from the Bill Crow Archive