In our film, jazz is not only a unique musical genre

that emerged in America in the early 20th century but,

above all, an embodiment of Freedom—

in music, self-expression, and attitude toward life

The Beginnings

Soviet jazz emerged in 1922 when the debut of the first domestic jazz ensemble, a so-called "jazz band," took place in the Soviet capital. The premiere was held in mid-autumn of 1922 in the Great Hall of the State Institute of Theater Arts. The honor of popularizing jazz in the USSR initially fell to Kharkiv native Yuliy Meitus and Moscow-based Leonid Varpakhovsky, who organized ensembles inspired by the music they heard during the 1926 tour of American jazz bands led by Frank Withers in Soviet Russia. In the same period, the operetta "Chocolate Kiddies" was performed in the USSR, with Sam Wooding conducting the orchestra.

In 1927, Alexander Tsfasman formed the musical ensemble "AMA-jazz" in Moscow, while in Leningrad, Leopold Teplitsky created his jazz orchestra. These two ensembles marked the beginning of professional Soviet jazz. Their concert programs largely consisted of Western compositions. The People’s Commissariat of Education even sent Teplitsky to the United States, where he studied music for silent films and was particularly impressed by Paul Whiteman’s orchestra, known for its symphonic jazz style.

In 1929, Boris Krupyshev and Georgy Landsberg founded the "Leningrad Jazz Chapel" in the northern capital, performing Western pieces and original compositions by young Soviet composers such as Nikolay Minkh, Heinrich Terpilovsky, Alexei Zhivotov, and others. This ensemble existed until 1935. In early 1929, trumpet player Yakov Skomorovsky and actor Leonid Utyosov from the Leningrad Theater of Satire created the "TEA-jazz," presenting jazz in a theatrical format with its own script, hosting, dancing, and variety acts. The orchestra collaborated with composer Isaak Dunayevsky. Around the same time, Alexander Varlamov, Alexander Tsfasman, Georgy Landsberg, and Yakov Skomorovsky established jazz ensembles that shone on the Soviet jazz scene and began recording records.

During the 1930s, Soviet jazz orchestras increasingly performed pieces by Soviet composers such as Daniil and Dmitry Pokrass, Leonid Diderichs, Alexander Tsfasman, Alexander Varlamov, Yuliy Khait, Nikolay Minkh, Georgy Landsberg, and Heinrich Terpilovsky. Isaak Dunayevsky gained fame for his rhapsodies, while Alexei Zhivotov and Dmitry Shostakovich became known for their jazz suites. In 1938, conductor Viktor Knushevitsky and artistic director Matvey Blanter completed the creation of the State Jazz Orchestra in Moscow. Around this time, Alexander Varlamov founded the All-Union Radio Committee Orchestra, later led by Alexander Tsfasman. By the late 1930s, jazz could be heard on Soviet radio stations, and in 1940, Nikolay Minkh formed his orchestra at Leningrad Radio.

The History of Soviet Jazz

1940s and 1950s

When the WW2 began, Soviet jazz musicians, including Nikolay Minkh, Yakov Skomorovsky, Yuri Lavrentiev, Boris Rensky, Isaak Dunayevsky, Leonid Utyosov, Dmitry Pokrass, Klavdiya Shulzhenko, Boris Karamyshev, Viktor Knushevitsky, Alexander Varlamov, and many others, toured the frontlines with their orchestras. During this period, Vasily Solovyov-Sedoi composed the famous song "Evening on the Roadstead" and Nikita Bogoslovsky wrote "Dark Night." After the war, a variety orchestra of wartime jazz musicians was formed under the direction of Viktor Knushevitsky at All-Union Radio.

In 1946, Alexander Tsfasman worked to establish the large "Sympho-Jazz" orchestra based at the Hermitage Theater. After the war, jazz enthusiasts in Moscow flocked to the Metropol Restaurant to hear performances by the popular ensemble featuring Sergey Sedykh on drums, Alexander Rozenwasser on double bass, Viktor Andreev and Leonid Kaufman on piano, Yan Frenkel on violin, and Alexander Rivchun on tenor saxophone and clarinet.

The late 1940s is considered one of the most challenging periods in Soviet jazz history. This was the era of the fight against "cosmopolitanism," targeting the influence of "bourgeois" Western culture. On February 10, 1948, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU issued the infamous decree "On the Opera The Great Friendship by Vano Muradeli," condemning the "formalist direction foreign to the Soviet people." This initiated a hunt for anything that could be labeled as "bourgeois" art, which naturally included jazz as "Western" music. Interestingly, jazz was never officially banned, even at the height of the anti-cosmopolitan campaign. However, jazz musicians and ensembles faced harsh "criticism," which amounted to severe persecution, and certain instruments associated with jazz were even banned. This persecution only ceased with the beginning of Khrushchev’s "Thaw."

In the 1950s, Vladimir Rubashevsky founded a dixieland band in Moscow, specializing in jazz standards and compositions by Soviet composers.

Around the same time, Oleg Lundstrem arrived in Moscow with his jazz orchestra, originally based in Kazan. His ensemble performed both original compositions and jazz pieces inspired by folk motifs. Starting in the late 1950s, Lundstrem and his orchestra relocated to Moscow, and they quickly became recognized as one of the finest jazz ensembles in the country. In the 1950s, Matvey Blanter and Isaak Dunayevsky composed songs that entered the golden repertoire of Soviet jazz. Other composers, including Boris Mokrousov, Nikita Bogoslovsky, and Vasily Solovyov-Sedoi, also wrote compositions for orchestras, often lighthearted or humorous, which were performed by both large ensembles and improvisational "combo" groups. Additionally, Soviet composers such as Vano Muradeli, Andrei Eshpai, Arno Babajanyan, and Tikhon Khrennikov composed songs for orchestras during this period.

1960s

In the 1960s, Soviet jazz began a new phase of development, establishing itself as not only an entertainment genre but a respected form of musical art. Jazz started being studied in music schools and conservatories, with new styles and branches emerging. Jazz compositions began to incorporate the folk music traditions of the Soviet republics, and the skill level of Soviet musicians improved significantly, with large orchestras showcasing more refined ensemble work. A generation of young musicians emerged, mastering improvisation as proficiently as their foreign peers.

One prominent group from this period, the "Golden Eight," included drummer Alexander Salganik, pianist Yuri Rychkov, trombonist Konstantin Bakholdin, trumpeter Viktor Zelchenko, and saxophonists Alexey Zubov and Georgy Garanian. They performed in the Central House of Art Workers orchestra, initially led by Boris Figotin and later by Yuri Saulsky. This orchestra won a silver medal in a jazz competition at the 6th World Festival of Youth and Students in Moscow, where Soviet musicians had the chance to interact with international jazz artists.

In 1958, a jazz club was established in Leningrad, followed by one in Moscow two years later, with support from local Komsomol committees. These jazz clubs quickly spread across the USSR, forming networks that hosted jazz ensembles, lectures, and sessions for studying foreign and Soviet jazz music.

The 1960s also saw the formation of notable jazz groups. Young people attended concerts by the Leningrad Quintet led by Vladimir Rodionov, Yuri Vikhariev’s quartet, and traditionalist bands like "Doctor Jazz" and "Seven Dixieland Boys." These ensembles performed music by Soviet composers, arranged their pieces, and composed original works.

At the same time, amateur jazz groups began to emerge across the Soviet Union, serving as a training ground for future professionals. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, small "combo" ensembles featuring members from the "Golden Eight" began recording sessions. These sessions, involving Moscow pianist Boris Rychkov and Leningrad trumpeter Herman Lukyanov, became the first professional recordings recognized as part of the new wave of Soviet jazz.

Esteemed Soviet composers began welcoming prominent jazz musicians into their professional union. Among these were notable figures such as Valter Ojakäär, Uno Naissoo, Konstantin Orbelyan, Yuri Saulsky, Vladimir Terletsky, Vladimir Rubashevsky, Murad Kazhlaev, Igor Yakushenko, and Bohdan Trotskyuk. Their works were recorded on vinyl, broadcast on Soviet radio, and performed at concerts.

From the 1960s onward, Soviet musicians participated in jazz festivals across the USSR and in the post-Soviet space. Renowned festivals included those in Tbilisi, Novosibirsk, Donetsk, Yaroslavl, and Leningrad. In 1967, Tallinn hosted Soviet jazz ensembles along with performers from Switzerland, Finland, Sweden, and Poland.

In 1962, the first international tour of a Soviet jazz group, featuring Nikolai Gromin, Andrei Tovmasyan, and Alexey Kozlov, took place at the Jazz Jamboree festival in Warsaw. After that, Soviet musicians began regularly touring abroad. During the Soviet era, artists like Anatoly Kroll, Konstantin Orbelyan, Oleg Lundstrem, and Vadim Lyudvikovsky performed with their orchestras in the capitals of Czechoslovakia and Poland, while "Leningrad Dixieland," Nikolai Gromin, and Georgy Garanian with their ensembles gained popularity in Prague.

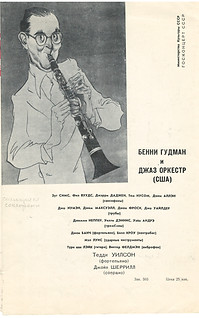

The Benny Goodman Orchestra Tour in the USSR

In 1962, the legendary American clarinetist Benny Goodman embarked on a groundbreaking two-month tour across the USSR with his orchestra. Goodman and his band performed a total of 32 concerts in Leningrad, Moscow, Kyiv, Tashkent, Tbilisi, and Sochi, drawing over 180,000 attendees. Soviet audiences greeted and bid farewell to Goodman and his musicians with standing ovations, calling them back for encores up to ten times. The crowd often refused to leave until the lights were turned off. The orchestra members were stunned by the warm reception, as none had anticipated such a response. Goodman himself was fascinated by the fishing, the majestic concert halls, and the Russians' "sense of swing." Among the audience members were notable figures, including Nikita Khrushchev and Alexei Kosygin, although Khrushchev reportedly left after the first set, complaining that "these jazz tunes" gave him a headache.

Soviet jazz musician Sergey Lavrovsky recalls: "The arrival of Benny Goodman's orchestra in Leningrad in June 1962 was perhaps the most significant event in the entire history of our first jazz club. It was a revolutionary moment for jazz, not only in Leningrad but throughout the USSR. The musicians’ visit gave us a huge boost. Of course, we tried to connect with the musicians; we were eager to speak with them. But a jam session with the Americans was out of the question. So we decided to arrange one in secret, at night, at the university. We brought our instruments—pianos, drums, a double bass—and snuck the Americans in by boat. The jam session went on until they couldn’t sit any longer. It was an incredible experience; we got to see how American musicians played compared to our local stars."

The jam session at Leningrad University was an unofficial highlight, made possible largely through the efforts of pianist, composer, and jazz enthusiast Yuri Vikhariev, the club president and a passionate jazz advocate. In his book, Memories of Jazz, Vikhariev shares: “Our joy knew no bounds, even though many musicians were initially disappointed by the choice of Goodman for this historic tour—why not Armstrong, Ellington, or Fitzgerald? Still, when we learned of Goodman’s lineup, excitement replaced disappointment: trumpeter Joe Newman, saxophonists Phil Woods and Zoot Sims, trombonist Jimmy Knepper, and drummer Mel Lewis! We were filled with anticipation."

One of the tour's most notable events was a midnight jam session at Leningrad University, organized by jazz fans who spirited American musicians from a concert at the Astoria Hotel to the university under cover of night. There, they played jazz standards like "How High the Moon" and "Avalon" until early morning, despite repeated attempts by the university guard to end the session.

Soviet saxophonist Gennady Golshtein, known as “Charlie,” shared his thoughts: “That night, we truly experienced swing. As soon as the Americans joined us, everything came alive with rhythm and energy. We learned so much just by watching and listening, as they gave jazz a pulse and meaning we had never achieved on our own.” This secret jam session became a legend among Soviet jazz musicians, demonstrating the energy and artistry of American jazz firsthand.

Following the tour, Gennady Golshtein sent his compositions to New York with the help of American musicians. In the following year, New York jazz stars Vic Feldman, Phil Woods, and Zoot Sims played his pieces on Radio Liberty, referring to Golshtein anonymously as "a Soviet jazz composer" to avoid repercussions for him back in the USSR. Later, they released an album titled Vic Feldman and the Stars Play the First Soviet Jazz Album, marking a unique crossover between Soviet and American jazz.